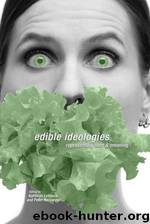

Edible Ideologies Representing Food Meaning by Kathleen Lebesco Peter Naccarato

Author:Kathleen Lebesco, Peter Naccarato [Naccarato, Kathleen Lebesco, Peter]

Language: rus

Format: epub

Tags: aVe4EvA

Publisher: State University of New York Press

Published: 2008-08-13T20:00:00+00:00

Eric Mason 119

historic context of the dish’s and the region’s history, which include the histories of oppressed groups within Spain such as the Sephardic Jews.

Claudia Roden writes in her introduction to The Book of Jewish Food that “Every cuisine tells a story. Jewish food tells the story of an uprooted, migrating people and their vanished worlds” (1996, 3). The Jewish diasporas, beginning with the destruction of the Second Temple in the first century AD, undoubtedly contributed much to the current diversity of Jewish cuisine. According to Stuart Hall, the field of cooking is an “incredibly diverse field because it is a diasporic field” (1999, 212; emphasis in original). But the texts through which most readers come into contact with traditional Jewish cuisine—cookbooks—are predominantly texts whose primary goal is functional. In most cases, Rona Kaufman claims, the meaning-making potential of cookbooks “never goes beyond the boundaries of its accumulated ingredients” (Kaufman 2004, 433).

Despite their underdeveloped potential, cookbooks have been studied as historical documents due to their capacity to “reflect shifts in the boundaries of edibility, the proprieties of the culinary process, the logic of meals, the exigency of the household budget, the vagaries of the market, and the structure of domestic ideologies” (Appadurai 1988, 3). But we cannot be satisfied with the language Arjun Appadurai uses here that suggests that cookbooks merely “reflect” historical and ideological forces. Cookbooks are active sites of the production of difference. The otherness of Sephardic cooking in Jewish cuisine, in many cases, is built on the same logic of difference that justified the Jewish diasporas. To deny the productive power of these representations is to participate in what Thomas R. West calls “historical amnesia,” forgetting that “processes of cultural differentiation have always involved wrangles over real stakes that affect people’s lives and the power to constitute reality” (West 2002, 12).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32018)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31941)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16026)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14506)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14075)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13370)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13363)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13239)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9342)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9291)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7313)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6621)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6279)